WELCOME TO THE SPCP

Setting Industry Standards & Supporting Members

The Society of Permanent Cosmetic Professionals is a non-profit organization that is dedicated to establishing the highest industry standards in permanent cosmetics, ensuring excellence, integrity & support of our members.

The Society Of Permanent Cosmetic Professionals

Leading the way in the permanent cosmetic & tattoo industry.

Become a CERTIFIED PERMANENT COSMETIC PROFESSIONAL

The SPCP offers an industry specific exam to achieve CPCP status. This designation satisfies USA state licensing and is recognized world-wide.

The Society Of Permanent Cosmetic Professionals

Leading the way in the permanent cosmetic & tattoo industry

Become a

CERTIFIED PERMANENT COSMETIC PROFESSIONAL

The SPCP offers an industry specific exam to achieve CPCP status. This designation satisfies USA state licensing and is also recognized world-wide.

ABOUT THE SPCP

Elevate Your PMU Game

to New Heights!

MEMBERS BENEFITS

See What Our Members Enjoy

Community

Unlock the gateway to exclusive networking & support! As a member, you will have access to our private online community, where you can share posts, spark discussions, and forge valuable connections with industry insiders.

Advisory

The SPCP also provides you with the most recent industry news and essential regulatory changes for your career advancement. All Members have the opportunity to connect with industry leaders & we are here to help.

Learning Events

Gain access to special online live events with leading industry experts!

Visit our online learning centre with discounts on courses created by SPCP Trainer Members.

Suppliers Discounts

As a member you will have access to exclusive offers from our SPCP Supplier members.

Certification

Achieve CPCP designation, and proudly display the acronym after your name. The CPCP demonstrates a distinct level of knowledge and dedication to the industry and CPCP certificants are held in the highest regard by industry peers and clientele in this very competitive industry.

Conventions

You will have the opportunity to attend annual SPCP conventions. Here you will gain insights from top industry leaders and connect with key professionals.

SPCP SIP 'N' SHARE LIVE PRESENTATIONS

7pm (CST) Every 2nd Monday of the month in 2025

Join us for presentations from top industry leaders with opportunity for discussions & questions.

These online live events are FREE to SPCP members and can be accessed via your members portal events page at members.spcp.org

NEXT SIP 'n' SHARE: Monday May 19, 2025 at 7pm CST

PRESENTER & TOPIC: Understanding Anesthetics with Pam Neighbors, CPCP

E-LEARNING

SPCP Online Courses

Learning events & courses offered by the SPCP

Offered by the SPCP

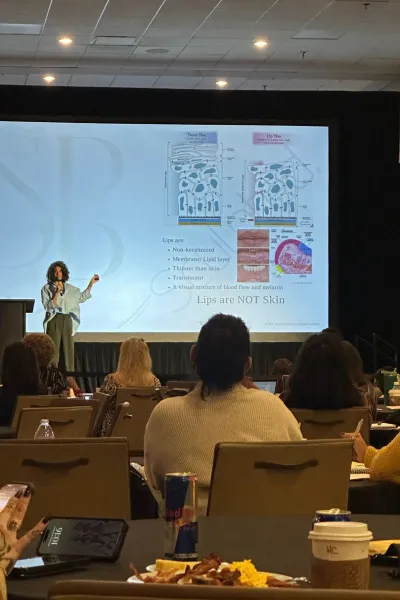

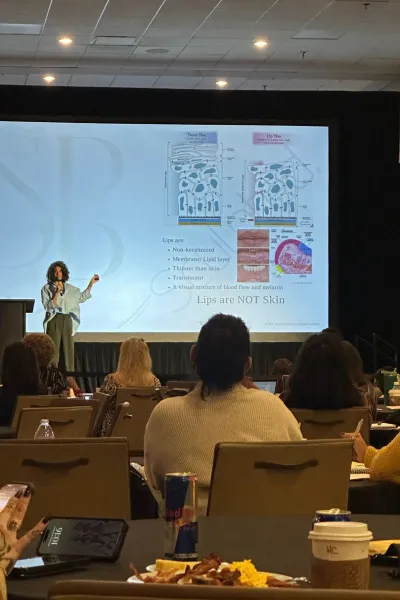

2024 Convention & Trade Show

Watch the replay of the 33rd SPCP Annual Convention that was held live in Dallas, TX in 2024

11 Presenters plus 4 bonus vendor presentations

16 CEU's

1 Year Access

499.00 USD

Discount for members if purchased from Members Portal.

Offered by the SPCP

CPCP Exam Review

Hosted by Judith Culp Pearson CPCP

Live Zoom Session to help candidates prepare for the CPCP exam..

Next Session

Tuesday May 6th, 2025 at 6pm CST

90 Minutes

$195.00 USD

Offered by the SPCP

Train The Trainer Online

Pre-Requisites: SPCP Professional or lifetime membership & CPCP designation.

Available April 2025

16 Hours

Certificate of CEU's

$495.00

Get Involved!

Successful Non-Profits rely on volunteer support and the SPCP would love to have you help grow our organization.

Explore the endless possibilities to be involved with the SPCP

Committees

Conventions

Social Media

Represent

Committees & Conventions

Social Media & Represent

Our Sponsors

GOLD SPONSOR

SILVER SPONSOR

BRONZE SPONSOR

2024 Convention Sponsors

TEACH ME PMU, Angela Torresi

CHANCO BEAUTY, Pat Shibley

AFTER INKED, Andrea Gerber

PERMABLEND, Anne Marie

PMU MARKETER, Jake Randolph

GRIP NEEDLES, Alexa Dalton

EVER AFTER PIGMENTS, Sean Brown

BROW SISTER, Victoria Racca

MICRO TATTOO, Ang

JENN BOYD INK, Jennifer Boyd

THE VAULT BEAUTY CO, Saville Warren-Pena

VICKI'S MAKING FACES, Vicki Hansen

VMM, Vicki Martin

GIRLZ INK, Teryn Darling

ZENSA SKIN CARE, Nabil Khan

TINA DAVIES PROFESSIONAL, Tina Davies

LIVELY INK, Terry Lively

EYES BROWS LIPS, Sandra S

NA SENG, Na Seng